PHILOSOPHER, RESEARCHER

MATHIJS DE BRUIN

Mathijs de Bruin is studying potential paths towards a future where humans happily coexist with their environment. With a background in philosophy, physics and IT, his perspective is that societal decentralization and increasing ecological and cultural diversity might allow our species, and our planet, to survive the impending collapse of socioeconomic infrastructures and sustaining ecosystems. To explore these ideas, Mathijs initiated the Decentralized Society Research Project to be part of the foundation of a sustainable living community in which ecological, cultural and economical benefits are maximally aligned, resulting in a negative ‘less than zero’ environmental impact.

TERMS

grace

diversity

autonomy

societal

decentralization

NEW ECOLOGIES

GRACE

Grace is a fundamental aspect that is missing in our conceptual framework of society. If you search the internet for images of grace you will find women in graceful poses, but not a deep understanding of beauty and the worth of things. The ultimate value of things doesn’t stem from external value.

URBAN ASSETS

DIVERSITY

We currently live in a global monoculture at the scale of the planet. There are small areas, like cities, where lots of cultures blend, but the local, regional and tribal culture, and the true diversity have been lost. The reigning norm is the capital.

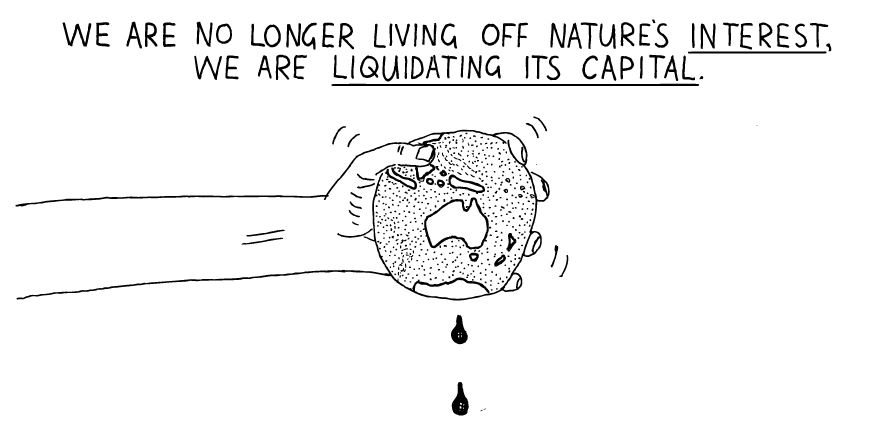

Our food has become very monotonous. The food that most people eat differs from what rich urbanites consume, which is very nice but not accessible to most people. By producing our food in monocultures, we eat mostly corn in different forms. In this way we make ourselves very vulnerable to exploitative systems but also to diseases. If there is a disorder somewhere in our food chain, we all have a huge problem, and these things do happen. So for reasons of resilience, I think biodiversity is essential.

DIGITAL TOOLKIT

AUTONOMY

Autonomy is another very important aspect. We live in a society where most of our governing structures are centralized and hierarchical with lots of decisions made from top to the bottom, but very few structures going from the bottom up. The managerial revolution has played huge role in this process. The management has taken over large aspects of the political domain, which used to be about values, and now are about efficiency and profit. With social technology, combining IT and people forming collectives, we can actually re-create a large part of the traditional function of the state. We could organize education, resource distribution, solidarity and care. All these things can be done on a much smaller scale, where the people involved in these facilities are directly involved.

NEW COLLECTIVES

SOCIETAL DECENTRALIZATION

Societal decentralization is one of the ways to express and potentially realize more abstract values. I’m thinking of peer to peer based structures where you create symmetrical interdependence, where people are dependent on other people, who are at the same time dependent on the same people. This is a network with inherent resistance against creating stronger hierarchies.

INTERVIEWED BY

ANIA MOLENDA

Exploring the potentials and drawbacks of a new vocabulary with Mathijs de Bruin, we discussed over-rationalization, the value of nonhierarchical structures and how being aware of our own privileges could help us limit inequalities.

book

MANUEL DE LANDA

‘A Thousand Years

of Nonlinear History’

AM:

As this project is about vocabulary and communication, what do you think is the state of the vocabulary we currently use? Are there problems with it and is there something that we have to change about it?

MdB:

One aspect that is typically overseen in most western cultures is the tendency to over-rationalize. There are a lot of aspects that due to the way we structure information and conceptualize our perception remain hidden. For most people it takes a lot of effort to realize this simple fact and to connect it to daily actions. A lot of spiritual traditions focus on awareness, mindfulness or maybe even heartfulness: connecting with the rest of our being without the formulation of thoughts or concepts, and allowing ourselves to shift perspective. I find this very important, especially in the arts and sciences. We need this kind of movements if we want these disciplines to be useful for society, rather than just remaining in a circle of recitation.

Another aspect is alienation. In Dutch we use the word ‘vervreemding’, which has the double meaning of literal alienation but also of dispossession. Typical urban structures and relationships between the urban and the rural domains are exploitative. This is a historic phenomenon and we need to be aware that when we go to any shop to buy anything, our action causes disproportional harm to the people who produced this product. Being aware is the first step towards coping.

AM:

You mention the idea of re-citation, being always in the same cycle. Have you experienced a situation where you were trying to communicate and you were not understood or the other way around, where you were outside your own circle of citation and it turned out to be very inspiring?

MdB:

I was trained as a physicist and I developed a deep fascination for the ways physics provides interesting insights in society and systems in general. But quite early in my studies I realized that in order to be part of the scientific community I would need to respect the strong power hierarchies that are embedded in this system, be concerned with optimizing my exposure, and make sure my work is quoted by people with high impact. It is not about making meaningful research that contributes to society. Additionally, in this field, one is often forced to stay focused in a very narrow domain, a phenomenon that is currently changing, yet at a pace too slow to cope with the societal changes that are necessary. Think for example of ecology. When I started it was not possible to do a broad ecology-based study. Sociology, economy and other sciences were often not considered hard sciences and the fact that these studies now exist and are becoming increasingly common is telling of this shift. Interdisciplinary sciences will be the domain where innovation and actual solutions to real world problems will be found.

Interdisciplinary sciences will be the domain where innovation and actual solutions to real world problems will be found.

AM:

Is there a concrete example of understanding terms differently across disciplines that comes to your mind?

MdB:

I have a big interest in Buddhist philosophy, where one can find the concept of prana or ch'i, which is a life energy pervading things, that is very concrete, material and touchable. In physics there is also, of course, the concept of energy, but as an entirely abstract idea. In most physical models it is a number that only matters in relation to the energy in a different state of the system. When one tries to translate this to concrete things, such as Tai Chi, one needs to work on a bodily and embodied practice.

There are some interesting problems with consciousness in relation to science. When I talk to people that are spiritual, we usually have very interesting discussions. But I ‘m afraid that many eco-activists and people that work towards changing society to be more sustainable lack this physical concept of energy. Even though they are two different notions, I think we need both.

The same goes for computer sciences: not being aware of what computers are, makes it hard to be critical about them and about automated systems in general. For example some eco-activists are reluctant to use advanced forms of technology but they are very willing to use archaic technology and the question is: are these fundamentally different? I consider asking these questions as part of my project.

AM:

In the example that you just mentioned, we can look at energy as pure calculation or from the point of view of spirituality. Would we understand each other more if we start to compartmentalize more or is it about a broader understanding of these terms?

MdB:

I think neither. Western people are strongly conceptually developed and we have a strong toolkit for handling concepts that are well delineated and properly defined, especially in philosophy. This is partly an unnecessary load we carry with us, because it keeps us from seeing other aspects. We should be more conscious about the simple fact of understanding, at least on a philosophical level and mainly for people who work with concepts on a daily basis. It would not hurt for them to be aware that they are working with concepts and that these do not have a fundamental meaning that is unchangeable. So just being aware of the process of conceptualization or the process of creating meaning and creating a vocabulary would allow us to understand our own vocabulary and the one of others, to shift meanings and play with them and understand each other a lot better, which is a fundamental aspect of being a part of our society.

So just being aware of the process of conceptualization or the process of creating meaning and creating a vocabulary would allow us to understand our own vocabulary and the one of others, to shift meanings and play with them and understand each other a lot better, which is a fundamental aspect of being a part of our society.

report

KAYLY OBER

'How the IPCC Views Migration'

Department of Geography,

University of Bonn

AM:

You talk about the value of mesh as opposed to hierarchical structures. Why do they have more value? Do you think mesh structures are something new or old?

MdB:

Let me briefly explain the difference between mesh structures and hierarchical structures. In mathematics a graph can be visualized as points with arrows to other points. Hierarchy is typically visualized as a tree, that has one root and it shoots up on and on. So that every point has multiple arrows pointing away from it. A mesh is typically a graph where most points are symmetrically connected to other points. A mesh could be seen as being spread out over space, with random connections between points. It looks like a more uniform structure. Usually in hierarchical structures, especially in societal, economical or social-economical contexts there are few points where information comes in and goes all the way down to the root node. Recently, and technology might have played a role in this, it has become possible to structure systems that do not require centralization. A well-known example is the blockchain that allows a trusted common history of events without centralization or the involvement of a third party. You could also look at hospitality in the form of bewelcome.org, trustroots.org, an exploitative service like Uber, or other peer to peer services that are already becoming popular among large parts of society. People are working on decentralizing the internet as well as trade systems. There are cooperatives that allow us to order food together directly from wholesale and the next step is to order directly from farmers. It is obvious to me that this makes more sense, both in terms of chain transparency, energy and cost efficiency.

At this point I would like to mention Manuel de Landa’s book ‘1000 Years of Nonlinear History’. This work contributed to my conception and understanding of the emergence of hierarchical structures under certain pressures, especially scarcity or other dynamics. The book points out how material pressures created incentives for centralization, in terms of capital but also in terms of urbanization, concentration of specializations in a small locality such as a city made sense and contributed to value creation in an efficient, structured and complex way. This is interesting but another aspect of it is that the material costs of these structures and their effects are exploitative in practice.

illustration

STEWART MCMILLEN

'Part of Nature

AM:

In your research you mention that we should use inequalities. You explain that they will always be there and we should work with them in different ways. Could we use inequalities in non-exploitative ways?

MdB:

Inequality results from a combination of free exchange of capital and leads to fundamental asymmetries. These two aspects are enough to create any kind of inequality. We could accept this fact and work with it. We could design systems of capital exchange that are designed specifically to limit inequality or we could accept inequality and try to decrease it locally to an amount that is healthy to a given society. In many cases people that have a lot do not mind sharing it. People in the Global North are rich and have more to spend than those in the southern parts of the world. These people do not consider themselves well off, because they are not aware of their privilege. We could think of direct trade relationships, e.g. food cooperatives where people can buy their food directly from the source in developing countries. This way a lot more money could arrive in these people’s hands. When people are aware of their privilege, they use it much more efficiently, and the impact can be much bigger. If you think that as one person you do not make a difference you should think that one person in northern Europe, or in the Netherlands in particular, pollutes as much as a few families in other parts of the world.

link

MATHIJS DE BRUIN

‘Decentralized Society Research Project’

AM:

And you think that this can turn into something positive rather than something negative?

MdB:

Human survival depends fundamentally on justice, on narrowing the gap between rich and poor and mostly on having the primary needs met for everyone. If we map the places where we can expect most of the CO2 contributions and where we can expect most of the victims of climate change, it becomes clear that we need to make it easier for people to have less children, to make sure that they will be taken care of when they are old or sick, to provide enough food, a roof, privacy and freedom to think. We can’t clean our local privileged urban environment without considering the ethical or moral aspects of resource intensity of these urbanities.

One of the triggers for me to start the Decentralised Society research project was a paper describing a mathematical model of societal collapse based on typical resource collapse patterns. There were several scenarios described, but it was clear that a sudden collapse could happen much earlier in a society with lots of resource distribution asymmetries and inequality. The way this would happen is that the poor remain at a level below self-sustenance until they disappear and the remaining rich eat each other. But these systems and structures can change with minimal energy, just by changing people’s minds about how they can use their power. They can use their autonomy to change much more than just their own life.