ECONOMIST

GIULIA PESARO

Is an economist, independent researcher, professor and consultant. She works in the fields of strategic planning for enhancing quality, resilience and the sustainable development of territories and local communities. She is a senior partner of Cooperate Srl and teaches at Politecnico di Milano and Università dell'Insubria.

TERMS

complexity

knowledge building

collaborative approaches

innovation

NEW ECOLOGIES

COMPLEXITY

We face complex situations, territorial frameworks and bodies. Urban areas are complex bodies but complexity is not a negative. It means the build up of many components that need to be understood both separately as well as together as a system. This is why complexity is challenging. We need so many different eyes to understand all the components that make up complex situations. We need to be able to move from the detail of a singular component up to the scale of the system and back, in a guided manner.

URBAN ASSETS

KNOWLEDGE

BUILDING

Knowledge building stems from this idea of complexity. In order to face complexity there is a need for knowledge building. We need to understand the components in order to identify and describe them. Sometimes we need to acquire new knowledge because the different shapes of components can form new complex bodies which necessitate new ways to put them together and understand them. So knowledge building and the sharing of that knowledge is essential to understanding complex systems.

DIGITAL TOOLKIT

COLLABORATIVE

APPROACHES

In dealing with complex systems one cannot think about operating alone, developing individual research or individual projects. We require far more people in order to be able to understand all of the relevant components within a project. Collaborative approaches will become essential for future work environments.

NEW COLLECTIVES

INNOVATION

My view is that real innovation comes from working in teams in order to bring together different perspectives and disciplinary approaches. Following the same path of enquiry allows a person to continue deepening their knowledge, but that knowledge remains drawn from that same path. In urban studies and urban planning what we really need are new, innovative and disruptive paths. We can only achieve this when we share our ways of looking at things with other people. Together we can see components that were previously ignored because our disciplinary approach caused them to be overlooked, and it is that overlooked component that could be the key to better understanding a complex system.

INTERVIEWED BY

GIANPIERO VENTURINI

We sat down with Giulia to discuss the importance of collaboration and systemic design in operating in complex urban systems as well as the possibility of revising our monetary understanding of value.

GV:

In your opinion, what defines a contemporary vocabulary? Is there anything you would change in relation to the vocabulary we use today? What would comprise a new vocabulary?

GP:

The formation of a new vocabulary is a really important and challenging project because words are used in so many different ways. When one word becomes popular we have to understand the various meanings behind this word. Consider the new words that are rising in our vocabulary – words such as sustainability, smart, green and resilient. What do these words mean exactly? Forming a new vocabulary can address these different understandings of meaning.

report

EUROPE 2020 GROWTH STRATEGY

Growth Strategy

European Commission

A new vocabulary not only establishes the definition of a term but also the term as a point of reference from which everybody can draw to influence their own work across disciplines. So these new words begin to define the ‘frame of actions’. We might make reference for instance to the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy’s use of the terms ‘smart, sustainable and inclusive’, which mean so many things but have the potential to remain relevant if they become clearer. There are also other words which define the respective toolboxes of different disciplines and here a clear vocabulary is even more important, to distinguish different tools and methods operating under the same names. For instance, ‘project design’ means very different things to an economist, an architect or a social scientist. This difference in meaning and setting the words defining these elements is very important to understand.

Look at the term resilience: is resilience so different from sustainability? Is resilience so different from smart? At first we talked in terms of sustainability, then came smart, and finally resilience arrived. Our final goal however, has always been to help urban areas to develop in an environmentally sustainable way, with high social quality among communities that are able to produce useful and intelligent new services for living in our cities.

Our final goal however, has always been to help urban areas to develop in an environmentally sustainable way.

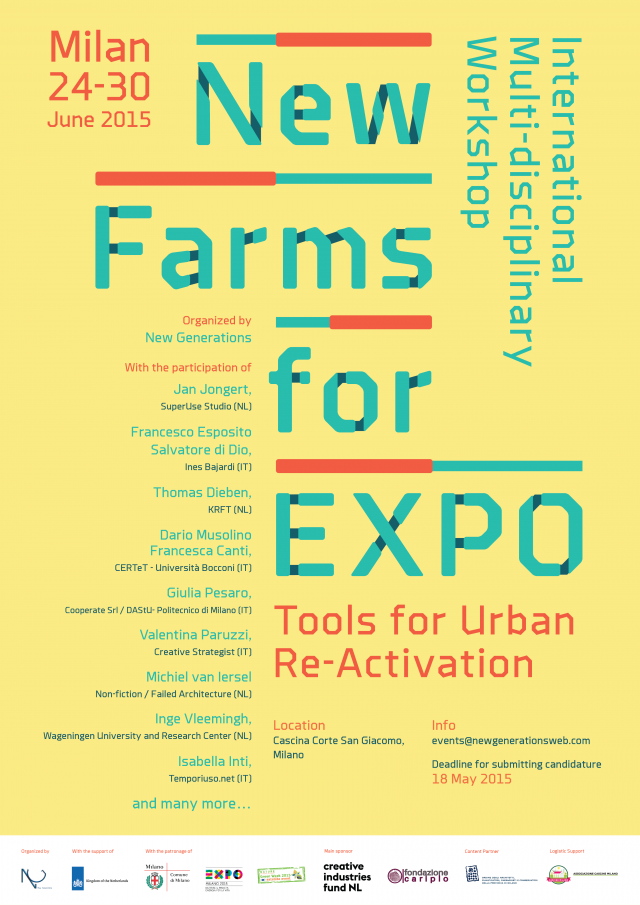

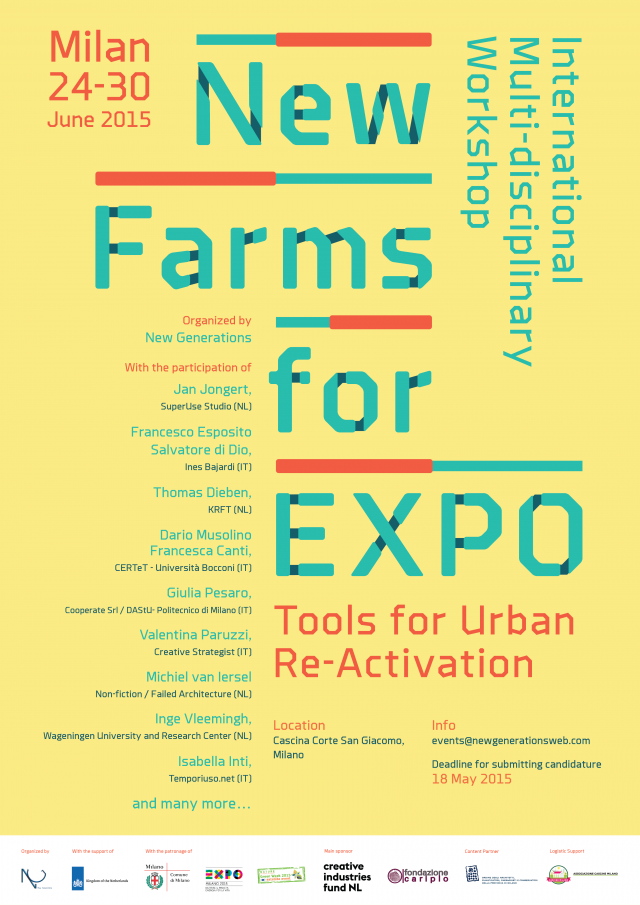

event

NEW FARMS FOR EXPO

A workshop for Milan Expo 2015

organised by New Generations

GV:

In your own experience, have you encountered any misunderstandings or different understandings of a term, when you have worked with other professions? How did these incidents evolve?

GP:

Having a degree in Economics and a PhD in public policy and land planning, I have often been part of interdisciplinary projects where these kinds of misunderstandings were common. After a lot of experience, I became a sort of a translator from one disciplinary language to the other, helping all the people involved understand the same things.

I had the opportunity to participate in a workshop at the 2015 Expo run by New Generations, called ‘New Farms’ , which looked at the regeneration of farms around Milan from an economic and architectural perspective. The architects talked about markets as physical places, offering and hosting activities, and thinking of them as functions within the built environment that were culturally evident. As an economist, I was thinking: “We can invest in restoring this cultural heritage with the goal to make these activities stable and functional over time.” Differing from the architect, I was looking at the market in terms of demand and supply, but we exchanged our ideas of ‘market’ and the results were very nice.

There is also a less positive but equally interesting example. I was asked to make a presentation about resilience in the agro-food sector at a conference. At a certain moment I mentioned ideas about markets and exchange. To some people I was speaking about money. The moment one mentions exchanges or economic relationships, some people automatically think: “this is just about money, this is not good”. To an economist like myself however, money is a measure for value, so that when we speak about value we understand the same thing. We urgently need to discuss this because if we don’t like money as a measure-unit then we should consider developing other measures of value.

To an economist like myself however, money is a measure for value, so that when we speak about value we understand the same thing. We urgently need to discuss this because if we don’t like money as a measure-unit then we should consider developing other measures of value.

GV:

Can you explain what you mean by Systemic Design already creating the conditions for a vocabulary of new terms, that makes together values, people or different kind of groups. Can you explain the concept of innovation in terms of relations? How can we understand the common ground and translate it into action?

GP:

Systemic design can mean many things. The main idea is of a system, that encompasses everything from the body to the environment, working simultaneously with its constituent components. Systemic design means to first identify and describe the system components then analyse their strengths and problems. Later on, we look for what we call opportunities and impacts - or negative externalities - that arise within the system. Systemic design is a challenge, because the components of the system can be described and classified differently each time, to result in a different model. However in the end, the model has to be implemented and the theoretical components have to become real with all their specifics and technicalities. For this, teamwork is important and systemic design cannot exist without it?

Systemic design will be able to answer problems in an ambitious way, approaching them from a holistic perspective. We could design a particular project in order to regenerate a single public square, but a square ‘belongs’ to a neighbourhood, the neighbourhood to a town, and finally, the town to a region. A system is made of components integrated into one another and so the scales of a project become critical in systemic design.

image

NEW FARMS FOR EXPO

courtesy of New Generations

GP:

Operating under such a design methodology, a new vocabulary becomes fundamental in facilitating new ways to create meaning. New terms will also arise to help diffuse new ideas. Knowledge and discussion are very important in achieving this. In urban studies, we should become more aware of other languages not only of our colleagues, be they engineers or social scientists, but also of the wider people we are working for. The languages of the communities. How can I communicate better with the community to make them understand the opportunity to relate differently to our built environment, to take care of it?

We often speak about circular, collaborative and smart economies. We also talk about community and green economies. These terms are integrated into the discussion of urban areas but they do not necessarily assist in making people understand these new terms in a different or better way. The economy, with respect to towns, cities and communities, needs to be better understood and operate differently to better target our the new emerging goals - smart and resilient cities producing for communities.

We often speak about circular, collaborative and smart economies. We also talk about community and green economies. These terms are integrated into the discussion of urban areas but they do not necessarily assist in making people understand these new terms in a different or better way.

GV:

What opportunities do you see for these varous languages of communities to influence perspectives on urban spaces?

GP:

New ecologies are important as they inherently refer to quality. We have attached specific ideas of urban quality to terms such as new ecosystem, green and the natural environment inside urban areas. Another element that is important, especially to me as an economist, is the need to contribute to a new urban ecology – the idea that nature inside the town can produce value and services. Green spaces, even very small ones can be considered green infrastructures - services available for the urban community. From an economic perspective, even a tree is a piece of green infrastructure, providing cleaner air and amenity, and I think it is very important to acknowledge this. We normally thinking of built areas as built-out’ . We have to consider the integration of nature into this complex system as green infrastructure. Of course, the true integration of green infrastructure requires a more complex approach to design and management of cities and I see management as critical to the real future of our cities.

GV:

How will this vocabulary assist new professions and experts that engage in the urban environment?

GP:

Concerning new professions and new ways of working, a common vocabulary will be very important, in terms of working in a team, encouraging fresh approaches and facing new problems and environment as well as also providing new terms for these new professions to define themselves through. My desire is that a new vocabulary will be the starting point of a new way of working together.