DESIGNER

YULYA BESPLEMENNOVA

Yulya Besplemennova is an independent multidisciplinary designer with a specific interest in the topic of hybrid space - social spaces existing in both the physical/digital, real/fictional realms - and intersecting fields of urban design, community engagement and interactions with technology.

TERMS

ecology of value

hybrid space

disrupting digital superpowers

tribes

NEW ECOLOGIES

ECOLOGY OF VALUE

Ecology of value is the study of what is value, how it is created, distributed and what is its relationship to bigger ecosystems like the urban. Sustainability thinking is currently focussed primarily on energy resources. However, it is the perceived value at this very moment which changes the worth of things and creates the real difference between the t-shirt made for 5 euro and the haut couture dress that is made for 5.000 euros. On an immaterial level, we can think of incorporating real issues into the ecosystem. This means the culture and even the feelings that human beings produce. It is not just about reducing human impact. People destroy the ecosystem and the planet, but we should also acknowledge that people bring a lot complexity and sophistication which should be preserved – this is the ecology of value.

URBAN ASSETS

HYBRID SPACE

Hybrid space is social space which exists across both the physical and digital realms. It is not only about the infrastructure and services that allow people to communicate online. It is also about how the communication and representation of the space is connected to its physical environment. The experience of people who go online or offline continues and it is necessary to manage this continuum. This continuity constitutes a new asset because it allows us to think about new curated content and experiences in space, transforming the public space into a new asset with a business model different than the one of the media platform. In this way it can become more self-sustainable.

DIGITAL TOOLKIT

DISRUPTING DIGITAL

SUPERPOWERS

The issue here is how people can use technology in the interests of society but also how problems might arise. Digital technologies give us some superpowers: we can see people in other places of the city and know what they’re doing, we can find out whether someone wants to date us even if we don’t see them physically. However, it is also the stage where we still don’t know if this technological superpower empowers individuals as it doesn’t mesh well with the structure of our society, its rituals and the policies that we have. It is really important to bridge the gap between the individual and the social empowerment.

NEW COLLECTIVES

TRIBES

It is important to think not just about communities and collectives but about opposing trends – such as trends towards tribalism. A tribe is a group which is defined by the same appearance, identity and especially rituals. The problem is that a tribe is not necessarily a cooperative collective. It is not a community of people trying to reach a common goal. Instead, in a tribe, people identify themselves with their group in opposition to others. The shared identity of a tribe is expressed through rituals. They can be both physical and online, as for example sharing something online, and this is how tribalism is very much connected to the disappearance of the public realm. People don’t meet others so often anymore. They are more connected to a group of friends both offline and on social networks. Online communities, forums and other platforms are replaced by networks the likes of Facebook or Twitter, where depending on your preferences, the service puts you together with people who are like you.

INTERVIEWED BY

GIANPIERO VENTURINI

Speaking with Yulya at the former site of Nevicata14 we discuss the enmeshed nature of the digital and the physical, how it has fed into her work, the creation of hybrid spaces and the formation of ‘tribes’.

GV:

How do you understand the idea of a vocabulary of terms and which characteristics do you think define the contemporary vocabulary in your field?

YB:

The last time I used a dictionary it was an Italian-English illustrated dictionary – the one where you have a picture of a tree alongside the words ‘tree’ and ‘albero’. It was a very entertaining way to improve my Italian! Instead, for communicating in my professional environment, I use much less of my vocabulary and more toolkits. When I want to explain something about the work I am doing, I usually send a service design toolkit where people can find not just the term but also the explanation of how to apply each tool, some relevant case studies and other related content. This way of communicating is different to the architectural vocabulary, which I used when I was about to enter architectural school. Though vocabulary was an interesting way to enter the architecture world and see a new profession, it was severely lacking references to reality and the actual applications of its terms and the ways they affected the practice.

GV:

Do you recall any positive or negative experiences you had with regards to communicating between different disciplines? For example, a moment when a word from a different discipline was totally incomprehensible or a moment when you discovered you were misunderstood?

YB:

A common vocabulary serves to bridge the gaps between disciplines and different specializations. I had many interesting experiences - I studied service design in Italy and in Italian ‘service design’ is called ‘design dei servizi’, but servizi can also refer to public restrooms, so I was often asked what exactly it is that I am doing. Service design is increasingly more acknowledged and people are getting more familiar with it in Italy but initially this was a common joke.

link

CERAMIC FUTURES

ceramicfutures.com

YB:

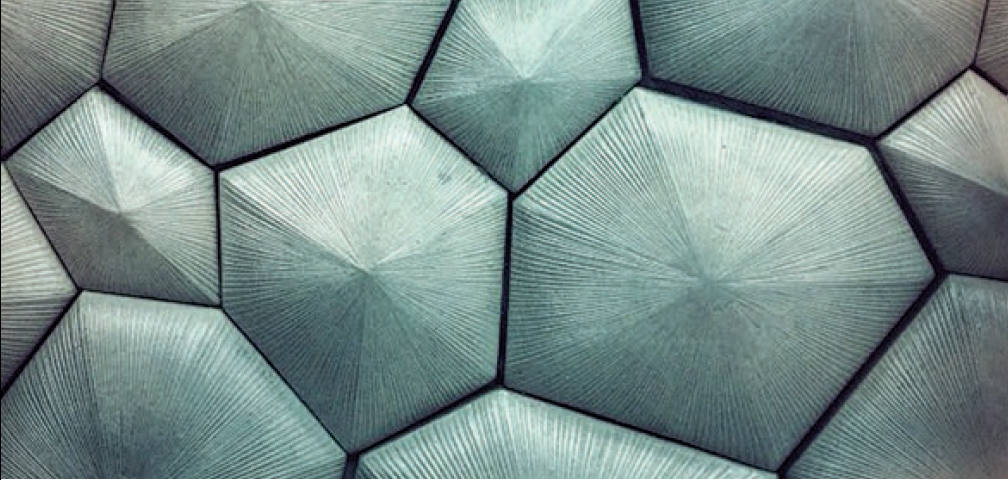

Another anecdote that I remember is from a project for ceramic futures, where we brought together students of design and architecture. The difference between their levels of understanding was considerable so our methodology was based on a design approach. For example, using terms like scenarios or trend research can be quite difficult for architects to understand. I have been thinking about that and eventually I came to the conclusion that designers are more time-based and architects are more form-based. Architecture can eventually last for centuries while designers think of the constant interaction between people and environment which happens in time, so it’s easier for them to understand the concept of scenario, future trend, storytelling or ritual. It is not only a question of vocabulary but also of the way people perceive things and ways to design differently. I cannot imagine an easier approach to aligning these perceptions, but the vocabulary people use to exchange opinions could be very useful to this.

image

CERAMIC FUTURES

courtesy of Ceramic Futures Work - From Dust to Ceramic Alexandra Coutsoucos

link

NEVICATA14

comune.milano.it

GV:

Can you talk about Nevicata14? Which terms would you use to explain this project?

YB:

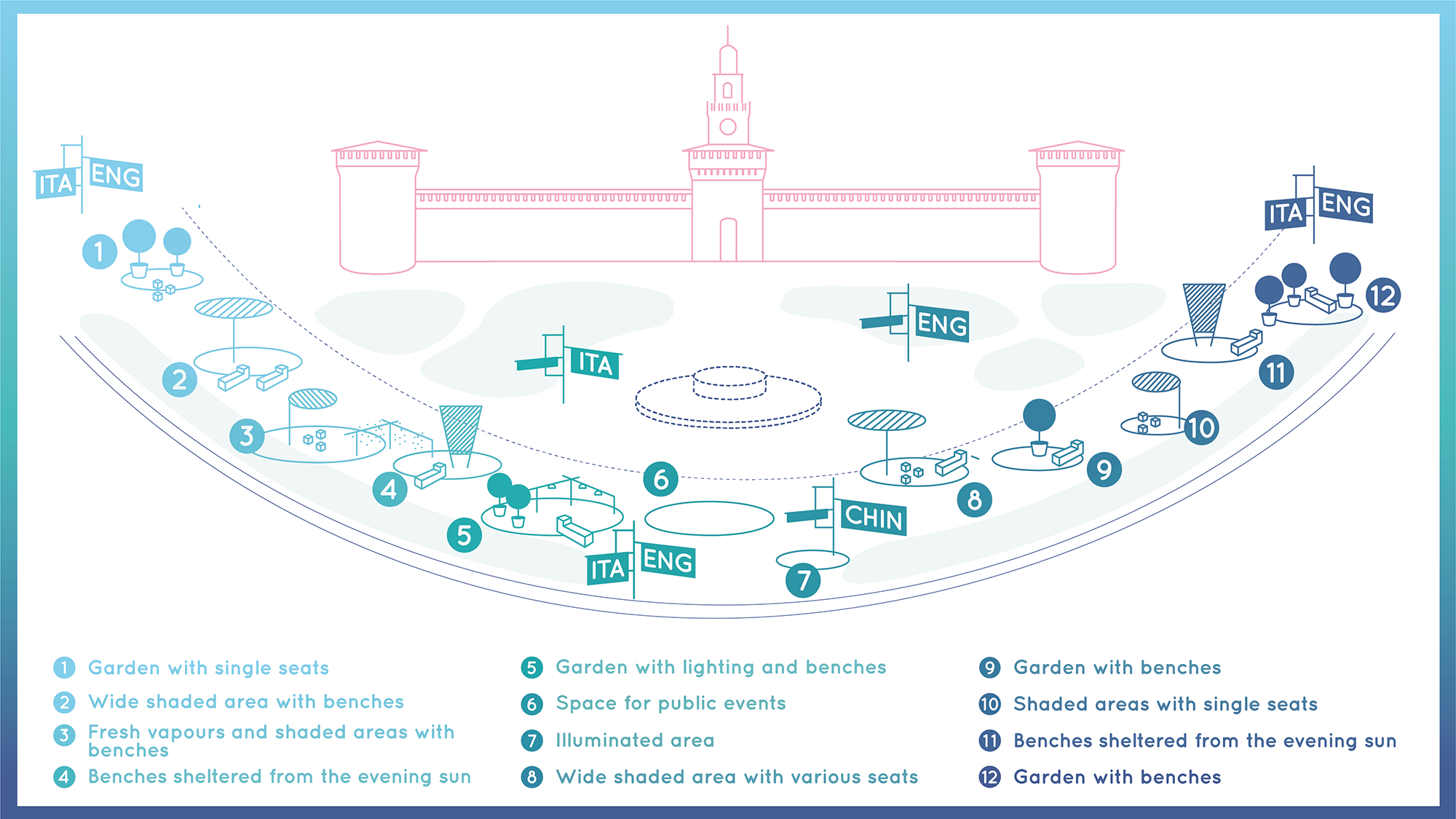

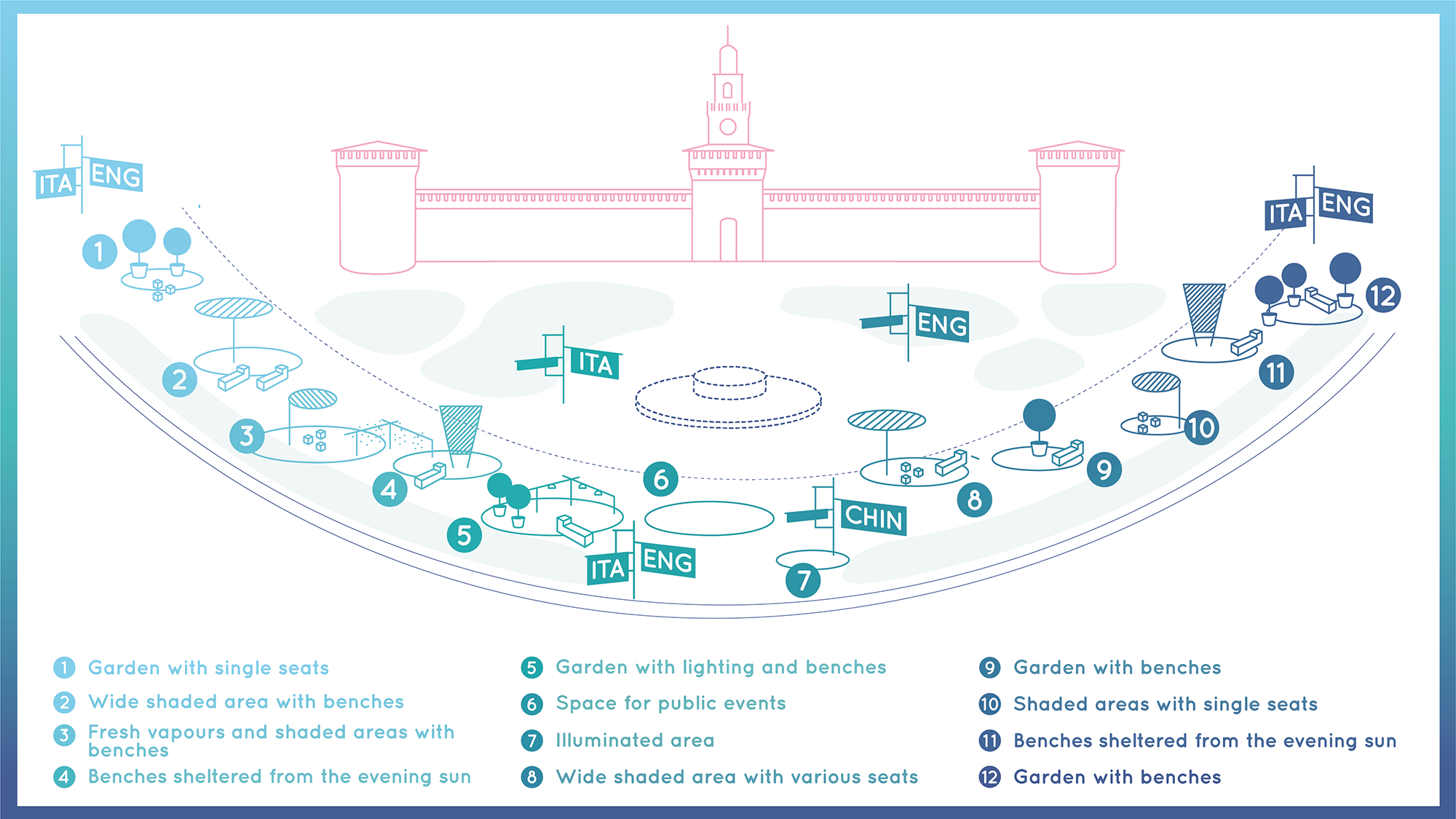

Nevicata14 was a temporary pedestrian configuration of Piazza Castello which happened as a response to the conflict around this space. However, it was not only an issue concerning the space but also the communication of the people involved. People suddenly discovered this place transformed without them being asked about it. Our task was to create a co-design process to involve people and help them work together. We started with digital tools as a necessary way to reach as many people as possible and to have higher visibility. Of course these tools have their limits, particularly with the older population, but actually they were very active there physically. It was very interesting because it established a common perception of the space as a hybrid space. Starting online on Facebook, we established a space where everyone could participate and tell their opinion before we launched the vision of the space as a shared experience. Nevicata means ‘snow fall’. The initial idea was to cover the space with a white material, which would reset the space to the state of a white page for everyone to contribute. We did a lot of work on the identity of this space because we understood that it was always misinterpreted. It is a square which was always used as a road. It was very important to detach it from the image of the Castello – to have not just Piazza Castello but Nevicata as a new destination. This is exactly how the levels of this hybrid space can come together to create a continuous experience, between the communication of people online and their experience of visiting the space offline.

image

NEVICATA14

diagram courtesy of Interstellar Raccoons

YB:

The term ‘tribes’ was important for Nevicata. It is true that there is a community of residences that was very active in expressing their opinion, but this opinion was often directed at protecting their territory. We had to deal with lots of other people using this space, such as city-users and tourists, a lot of whom came because of the Expo that took place during that summer in Milan. These people cannot be defined as a community, but as certain segments, which would be like tribes: there are people who take selfies with the Castello, or others, who come after work for an aperitivo. To understand better who they were, what kind of space they needed and how their rituals are expressed in the space was very important for us in Nevicata.

GV:

What do you think is the added value of a project like Nevicata? Can participatory projects such as this, bring in new experiences?

YB:

Participatory processes following the Nevicata model could be very useful. There’s a huge difference between the Nevicata project and the Expo Gate that stands behind me. Aesthetically, they work in a similar way, and they were both claimed to be ugly by a lot by people online. However, the important part of Nevicata was the additional layer of communication that has constantly reflected what was happening. This helped a lot of people to understand that it was not just about the temporary physical structures; it was about new space and the new uses for it. Eventually the experiment finished with positive results so the space remains pedestrian and there will be a new competition for its final configuration. With Expo Gate, the communication process didn’t go that well, people were not very involved and the debate stayed at the level of its architectural value, how it looked or whether it distracted from the views of the Castello in front. These two projects, which are very close, were structured in such different ways. One was just put there by a star architect and the other emerged by people involved in all the steps of the process.

The important part of Nevicata was the additional layer of communication that was constantly open about what was happening. This helped a lot of people to understand that it was not just about the structures, it was about new space and the new uses for it.

GV:

In a recent quote you said: ‘We are constantly connected and communicating in a mediated way with our neighbours, holding and processing a huge amount of data in real time’. We can also use the expression ‘Tinder vs. bar’ as a translation of ‘digital vs. analogue’. What’s the potential of the combination of these notions that are seemingly opposite?

YB:

When we talk about the analogue and the digital in the city it is very important to understand we don’t live in just the physical or just the virtual anymore; they are all mixed. The internet affects the city not just in its digital layers, but also through new layers of connection and access that are created. We live in an environment where we are constantly connected and communicate in an immediate way via networks that produce a lot of information. Each of these points has consequences for urban space.

Our experiences cannot be described as just digital or physical anymore. One can stay at home and sit in front of a computer but can also go out, run, do something with their friends all while still being connected on both a digital and physical level. Contrary to the radio and telephone, digital communication technologies rely in general on screen communication. Someone defines the interface through which we communicate. We never connect with the whole person but with a partial representation of them. It is now easier for people to approach someone on Tinder, Facebook or LinkedIn instead of talking to people in public spaces. That’s sad of course, but it also creates a new level of freedom. These networks have their own rules so the new services like Uber, Airbnb or Facebook cannot exist without people using them. There is no value in the service itself without the actors involved in the network. This is a new way of organizing teams and services.

It is now easier for people to approach someone on Tinder, Facebook or Linkedin instead of talking to people in public spaces. That’s sad of course, but it also creates a new level of freedom.

YB:

Finally, in relation to big data, it is a difficult yet interesting topic because we are not yet capable of processing all the data but it can bring huge insights. For example all our ideas of social physics, and the study of the fluxes in the city, could be very useful to better structure spaces, squares and connections between people. The difficulty in making a distinction between digital and analogue can be visualized in the case of Tinder. Getting a date doesn’t happen in the bar anymore, Tinder happens at home and then you bring your date to the bar.

The disruption of hybrid space happens because there is something happening in the digital environment and in the physical. It happens exactly when these two meet, like in the case of Uber and Airbnb where they brought a digital layer to the physical. However, society doesn’t share the same speed of development; it is much easier to introduce new software than to change society. So it is about how we can still have an experience that improves our lives without bringing continuous problems because we need to chase after our technology.